Camp with Oil Rig (1930-1933)

When you look at this picture I bet you wouldn’t guess that it’s a Jackson Pollock painting. Long before he developed his iconic oeuvre in the “drip” technique, Pollock experimented in a more traditional style. Perspective, composition, light, and shadow are all concepts that he understood before closing his eyes and splattering paint on a canvas (I think that’s how he did it anyway). It’s logical that an artist who is trusted to stray so far from the norm, would be someone who first mastered the traditional skills of a painter. You have to know the rules to break the rules as they say. I’ve heard it said to cinematographers as well, but I wonder if today’s DP’s still need a traditional foundation in our craft.

He thinks you can show restraint while shooting digital. I say maaaaybe.

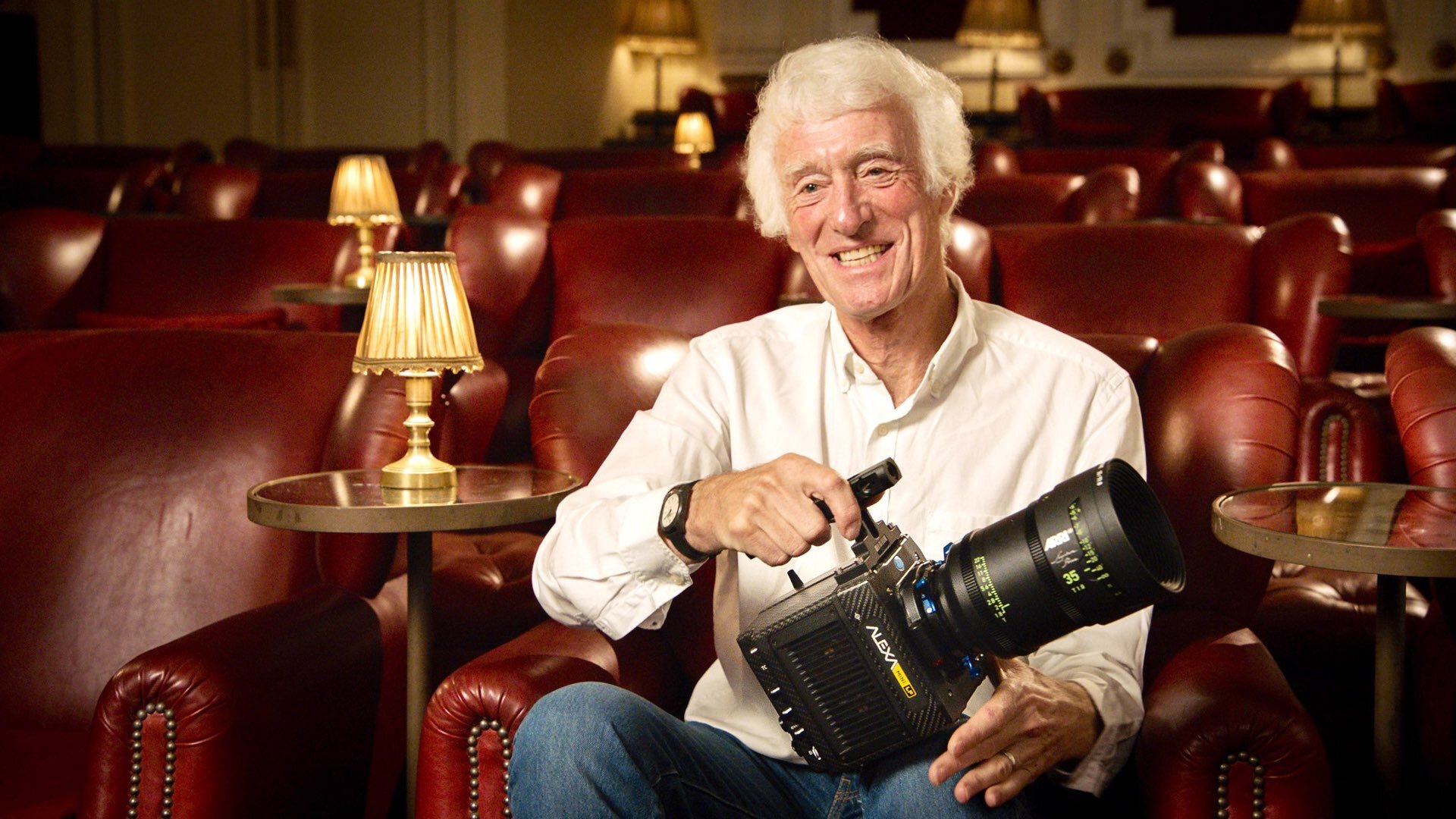

Sorry to rehash the film vs. digital debate, but it’s central to this question. Roger Deakins is very open about his preference for digital capture. The what-you-see-is-what-you-get nature of digital shooting can be a great advantage, but I think Deakins takes for granted the decades he spent with no option, but to shoot on film. The discipline that film demands is imbued into his bones as a filmmaker. Many young filmmakers now don’t know what it means to shoot a scene with only one mag left. That frugality wasn’t bred into them in their training. It’s easy to say that we can all adopt a disciplined on-set mentality, but it’s another thing to have no choice. You give it your best every take or run out of film.

Black & white is the past, not the future. Should it really be a challenge for so many of us?

When it comes to traditional skills, the discussion goes way beyond film vs. digital. In a recent interview cinematographer Antal Steinbach admits the challenges of shooting a movie in black and white by saying:

“I realized very quickly how subconsciously I use, and how we all use, color as separation. So when I was void of color I was having to tap into a place that was there, but it was difficult.”

This used to be the bread and butter of the cinematographer. The DP was THE person on set who pre-visualized the monochrome image. They knew where backlights were needed for contrast. Working in concert with makeup, wardrobe, and art departments they used texture, pattern, and scale to create depth. Now all that expertise is becoming a lost art. Are we okay with our cinematographers not having skills that used to be considered fundamental? Is that progress?

I’m not saying you can’t do this anymore, but…. good luck.

I think a lot about my regimented training in cinematography. We shot stills before motion, black & white before color, and mostly celluloid. We discussed movements in film history and what they contributed to cinema. But not everyone pursues a film school experience. We have cinematographers now who were introduced to filmmaking through iPhone cameras, gimbal stabilizers, and drones. On top of that, many traditional cinematographic techniques are now irrelevant. I recently saw Jack Cardiff’s Academy Award-winning cinematography in “Black Narcissus” (1947) and it’s a masterclass in how to get thrown off a set. He barrages a 60 year old actress with hard light, he’s got double and triple shadows on the walls, and for everyone except Zack Snyder the 1.33:1 aspect ratio is a nonstarter. As much as the classic techniques are important to understand, it seems like you can get more useful inspiration from the hottest music videos of the last few years than from half of the AFI Top 100. I understand that Cardiff was lighting for a Technicolor camera at around 12 ISO, but we have 2500 native ISO now. We don’t need to hamper young cinematographers with the burdens of yesteryear.

I’ve found great value in my education in cinematography and its history, but I can only see so far. We don’t know what possibilities are awaiting a generation of filmmakers who never knew older techniques. It’s exciting to watch DP’s who started out lighting with simple practicals instead of power-hungry tungsten kits and those who jumped right into aerial shots and steady camera movement from day one. I can’t wait to see what happens when we shed some of the wisdom of the old masters.

-Sheldon J.